By Edward T. Babinski

Vic (and a few others),

Something brilliant below about C. S. Lewis that you might enjoy (I didnʼt know the bit about “A Grief Observed,” is it true that Lewis published it anonymously and his friends suggested he read it before he ʻfessed up to being its author?). Ken Nahigian, whose work below I am forwarding to you, is one of my oldest and dearest internet buddies whom Iʼve known for decades. I published his response to creationism in my very first newsletter, Theistic Evolutionistsʼ Forum in the mid 1980s.

Cheers,

Ed

From: “Kenneth Nahigian”

To: “Edward Babinski”

Subject: Re: Edited collection of C. S. Lewisʼs final letters

Date: Wed, 14 Feb 2007 18:34:59 -0800Hi Ed. Fascinating! After all these years, Iʼm still a bigtime CSL fan. The little warts & blemishes only make him seem more real to me.

I do recall, from reading “Mere Christianity” many years ago (or was it “Problem of Pain”?), Lewis praising Zoroastrianism as making, to him, a fair amt. of sense, and the religion he would most likely take to if not for Xianity. And I know he loved mythology, but somewhat preferred the Mediterranean cycles (Greek & Roman) to the Norse strains (Celtic, Norse) that appealed to his pal Tolkien. You could see it in the Narnia stories — all those fauns and dryads.

Also fascinating to read his fears about declining writing ability when he was only 50. Heh-heh, maybe thereʼs hope for me, then. But imho, the most compelling thing he ever wrote, his truest voice and music, was his last book, “A Grief Observed”, after Joy Gresham died. He published it anonymously, and people kept recommending it to him. “This will help,” they said. So he finally ʻfessed up.

For your amusement, attached is a little essay on Lewis that I recently hacked out for my local Humanist club newsletter:

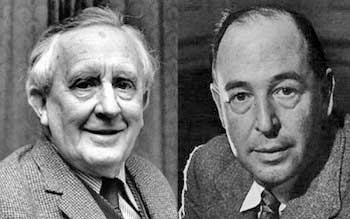

C.S. Lewis — In American Christendom he is a near icon, a poster-boy for conversion and a hero of apologetics-I know, having been a fan myself. A Monrovia, California, church window even sanctifies him in stained glass. In England his reputation is less luminous, more that of a peculiar, slightly eccentric propagandist for the Anglican church who also did a few things right: good studies of medieval poetry and some enjoyable childrenʼs books. What is his story?

Born Nov 29, 1898, Clive Staples Lewis had a traumatic childhood, made no easier by his motherʼs early death, a cold father and abusive treatment at Irish boarding school. A reluctant atheist at age 13-as he wrote, “angry at God for not existing … equally angry at Him for creating a world”-he developed, perhaps by way of escape, a love of myth, folklore and medieval literature, and of classics of literary fantasy. Deep in the pages, dreaming of magic, Lewis found a numinous emotion. He called it “joy.”

After a year at University College, Oxford, he enlisted in the British Army.

Age 19, his experience on the front line did not encourage belief in a good God-“the horribly smashed men still moving like half-crushed beetles”-and nightmares of it haunted him for the rest of his life.Wounded, mended, back in Ireland, Lewis found a brighter life. He returned to Oxford, where he graduated with honors and won a teaching post at Magdalen College. He found friends, mostly Christian believers. Long late-evening talks led him by nudges into a kind of intellectual theism. Christian Mythology, as he then called it, began to take on the haunting, numinous magic of his childhood readings. Two years later, on a long restless trip, a half terrified Lewis, aged 33, leapt over the threshold to Christianity.

He began to write: religious allegories, literary studies, childrenʼs fiction, apologetica, lectures, poetry, even Christian science fiction. He developed a congenial, easy-going style with compelling imagery. Before long he had a following. In the late 1950ʼs he met and married one of his fans, Joy Gresham, who suffered from bone cancer. Lewis was certain his prayers caused her remarkable remission-if it didnʼt work for others, well, they werenʼt doing it right. But Joy relapsed. In 1960 she died painfully. The result was a crushing crisis of faith, as well as some of Lewisʼs most heartfelt writings. After that, his own health began to decay.

He died of kidney failure on November 22, 1963. In the national news it was barely a footnote. John F. Kennedy and Aldous Huxley died the same day.

C.S. Lewis was a whirl of disparate elements, pagan, atheistic, modern and Christian; one reason he was such an effective apologist: he knew his audience, and could be all things to all people. But converted mostly by “joy,” he never deeply asked why it was Anglican Christian, not another faith. His favorite point was that either Jesus was mad-like “a man who says he is a poached egg”-or lying, or right. Jesus didnʼt seem like a madman or liar, so what he said all must be true. (Lewis liked this “trilemma” so much he put it in the Narnia stories: either Lucy is lying about Narnia, or mad, or saw what she said.) A slick argument, it forgets human character, our ability to compartmentalize. It excludes many middle alternatives (to name a few: Jesus misquoted, mistranslated, misspoken, misunderstood by later cultural eyes, engaging in mystic allegory, or falling into temporary ecstatic hysteria; or simply a tale that grew in the telling). It overlooks that Jesusʼ family did sometimes think he was mad (Mark 3:21,31-34). And it ignores other religious founders and teachers who said remarkable things, but who were not obvious outright liars, and palpably not poached eggs.

Lewis saw the Anglican Church not as just one way among others but the single cosmic truth extending from the farthest galaxy to his front porch. It never seemed to trouble him that this one staggering truth also happened, coincidentally, to be the formal faith of his own tribe, supported by English politics of his day and the university where he worked. His Christianity was parochial, English, Irish and Northern-even Roman Catholicism was alien to him, which much irked his Catholic friend J.R.R. Tolkien.

But most of what made Christianity joyful for Lewis seemed to be the pagan elements it got from its sources. So it may be his leap to Christianity was more of a slide back. And Lewis came to Bethlehem more by way of Narnia than the other way around.

Ken Nahigian, January 2007

From: “Edward Babinski”

Subject: Edited collection of C. S. Lewisʼs final letters

Date: Wed, 07 Feb 2007 01:57:10 -0500

Dear Vic (and a few others with whom I am sharing this missive),

There has just appeared an edited collection of Lewisʼs final letters, and I just read a fascinating little review of them published in the Washington Postʼs Book World. See further below.

Though a lot of the reviewerʼs comments were interesting, I especially enjoyed a few at the end, speaking of Lewisʼs “…genuine curiosity about Hinduism, his love of The Iliad, his endorsement of Zoroastrianism as ‘one of the finest of the Pagan religions,’ and his eagerness to see more recognition for the Persian epic The Shahnameh. He supported his elder stepsonʼs eventual entrance into a yeshiva. He didnʼt believe in word-for-word inerrancy of the Bible, saying that too few ‘know by the smell. . . the difference in myth, in legend, and a bit of primitive reportage.’”

Speaking of Lewisʼs metaphor about knowing things “by the smell…”

“Jaronʼs World: I Smell, Therefore I Think”

Did odors give rise to the first words? By Jaron Lanier

Discover Vol. 27 No. 05 | May 2006 | Mind & Brain

And see…

UCSD research ties brain area to figures of speech, grasping metaphors. 26 May 2005

Lastly, have you seen the latest Time magazine with lots of articles about the brain, all written by leading biologists and philosophers whose names weʼve both batted around before? Most of the articles are online at Time.com I know youʼll like at least one of the articles on the brain at Time.com, perhaps the one with the most miraculous tinge?

The Power of Hope By Scott Haig M.D.

Below is the review of the collection of Lewisʼs final letters:

The Lion in Winter: The inner life and last years of the man who created Narnia and explained God.

Reviewed by Cynthia L. Haven

Sunday, January 14, 2007; BW08

The Collected Letters Of C.S. Lewis

Volume III: Narnia, Cambridge, and Joy 1950-1963

Edited by Walter Hooper

HarperSanFrancisco. 1,810 pp. $42.95

In January 1949, when C.S. Lewis was only 50, he thought his life was over. “I feel my zeal for writing, and whatever talent I originally possessed, to be decreasing; nor (I believe) do I please my readers as I used to.” The unassuming Oxford don once said heʼd be remembered as “one of those men who was a famous writer in his forties and dies unknown.”

Then he began having nightmares about lions.

The Lion, the Witch and the Wardrobe, which was written quickly and published in 1950, became an enduring success. “I donʼt know where the Lion came from or why he came,” Lewis wrote later. “But once He was there He pulled the whole story together, and soon He pulled the six other Narnian stories in after him.”

Some of the eraʼs most magical childrenʼs literature and science fiction came from the pen of this unprepossessing professor of medieval and Renaissance literature; modern Christianityʼs most approachable and eloquent apologias were articulated by this former atheist. Yet despite international fame, to all external appearances, he led an uneventful, bookish life.

This last volume of his Collected Letters covers not only the Narnia novels but his brief marriage to the divorced American writer Joy Davidman; his major work of criticism, English Literature in the Sixteenth Century; and the overdue professional recognition he won when he was granted an endowed chair at Cambridge after years of snubs at Oxford, where he remained a lowly, overworked tutor.

Editor and friend Walter Hooper calls him “one of the last great letter-writers” — the last of a generation who did not lift a telephone receiver when he had something to say or tap out e-mails on a computer keyboard. Some of the recipients richly merited his ink: the detective novelist, theologian and Dante translator Dorothy L. Sayers; St. Giovanni Calabria of Verona (correspondence in Latin); T.S. Eliot; the sci-fi maestro Arthur C. Clarke; and the American writer Robert Penn Warren. In these letters, Lewis swaps quips in Latin and Greek and quotes Spenser, Statius, Beowulf, Horace, Wordsworth, Terence and Augustus. Other letters were from cranks, whiners and down-and-out charity cases; he answered them all.

“The pen has become to me what the oar is to a galley slave,” he wrote of the disciplined torture of writing letters for hours every day. He complained about the deterioration of his handwriting, the rheumatism in his right hand and the winter cold numbing his fingers. In the era of the ballpoint, he used a nib pen dipped in ink every four or five words.

The letters undermine the myth of a scholarly bachelor idyll. The enemies of peace were in his own household — especially Janie Moore, the mother of a fellow soldier killed in World War I, sometimes referred to as his “mother” and by Warren as a “horrid old woman.” “Strictly between ourselves,” Lewis wrote to a friend, “I have lived most of it (that is now over) in a house wh. was hardly ever at peace for 24 hours, amidst senseless wranglings, lyings, backbitings, follies, and scares,” he wrote. “I never went home without a feeling of terror as to what appalling situation might have developed in my absence. Only now that it is over (thoʼ a different trouble has taken its place) do I begin to realize quite how bad it was.” His brother Warrenʼs chronic drunkenness was the “different trouble.” Oxford was no refuge; when Lewis assumed the Cambridge post, it ended “nearly thirty years of the tutorial grind,” exhausting donkey-work that regularly burned 14 hours a day.

He summarized the net result: “I am a hard, cold, black man inside and in my life have not wept enough.” That problem, at least, was soon to be solved — taking us to the biggest riddle of his life. Lewisʼs romance, immortalized in the movie “Shadowlands,” is touted as one of the great love stories of the century. But as we read it in real time, Lewis more resembles a schoolboy who doesnʼt want to be seen walking home with a girl.

Itʼs not at all clear why. Joy Davidman had been a Yale Younger Poet, cherry-picked by Auden, and held a masterʼs degree from Columbia. Even Lewisʼs biographer and chum George Sayer, otherwise hostile to Davidman, describes her as an attractive, “amusingly abrasive New Yorker.” Yet Lewis, in letters, had clumsily referred to her as “queer,” “ex-communist, Jewess-by-race, convertite.”

Under her influence, Lewis wrote his finest novel, Till We Have Faces. Yet he worried that the quotation on the title page — Shakespeareʼs “Love is too young to know what conscience is” — might be too close to the dedication. “Otherwise, though the lady would not, the public might, think they had some highly embarrassing relation to each other.” Embarrassing? Like their wedding a week before, on April 23, 1956?

Davidman was diagnosed with cancer that summer, and Lewis finally ʻfessed up with a wedding announcement the following Christmas. “You will not think anything wrong is going to happen,” Lewis wrote to Dorothy Sayers. “Certain problems do not arise between a dying woman and an elderly man.” Problems? Like sex? At times, he seemed to pass the marriage off as an act of charity.

In a sense it was — but not in the way others guessed. Although many have impugned the motives of Davidman, the reason is revealed in a footnote: Lewis confided to his friend Sheldon Vanauken that he had married “to prevent the Government deporting her to America as a communist.” She had been a prominent party member, and the congressional red scare was in full swing when she fled the United States.

Yet within a few months, Lewis was writing to Sayers, “My heart is breaking and I was never so happy before: at any rate there is more in life than I knew about.” And elsewhere: “We are crazily in love.”

A miraculous three-year remission ensued, providing the most blissful episode of Lewisʼs later life. Davidman died in 1960. Lewis followed on Nov. 22, 1963, the day President Kennedy was shot.

A humdrum life? Hardly. But most will read these letters for more than Lewisʼs life story. Through the triumphs and anguish, the frustrations and bereavement, Lewisʼs letters unspool his spiritual autobiography.

Itʼs time to reclaim Lewis from the religious right, which has made of him an unlikely champion. The same audience would, perhaps, find it hard to square its adulation with his genuine curiosity about Hinduism, his love of The Iliad, his endorsement of Zoroastrianism as “one of the finest of the Pagan religions,” and his eagerness to see more recognition for the Persian epic The Shahnameh. They might be more surprised that he supported his elder stepsonʼs eventual entrance into a yeshiva. Lewisʼs religion was nuanced. He didnʼt believe in word-for-word inerrancy of the Bible, saying that too few “know by the smell. . . the difference in myth, in legend, and a bit of primitive reportage.”

In any case, Lewisʼs wry, erudite, often spiritually profound letters are too good to be co-opted. He could be a bit of a prig, but his inner life is no dusty relic, irrelevant to our world today. In fact, in an era of New Age fuzziness, his mental clarity refreshes.

Cynthia L. Haven writes for the San Francisco Chronicle, the Los Angeles Times and the Kenyon Review.

Speaking of Lewis…

Christopher Hitchens has a book coming out about religion, he also has let his opinion be known of C. S. Lewisʼs “Mere Christianity” in a little piece in Free Inquiry in 2006, titled, “C.S. Lewisʼs Hideous Weakness”. Itʼs not available online, but here are some excerpts I found at someoneʼs blog:

…I proceed to Lewisʼs classic nonfiction best seller, Mere Christianity. Taken a look at it lately? Try this:

First, there is what is called the materialist view. People who take that view think that matter and space just happen to exist, and always have existed, nobody knows why; and that the matter, behaving in certain fixed ways, has just happened, by a sort of fluke, to produce creatures like ourselves who are able to think. By one chance in a thousand something hit our sun and made it produce the planets; and by another thousandth chance the chemicals necessary for life, and the right temperature, occurred on one of these planets, and so some of the matter on this earth came alive; and then, by a very long series of chances, the living creatures developed into things like us.

On this evidence - which sounds like a semi-literate peasant stammering to repeat what heʼd heard of a very faint radio broadcast on Darwin or Albert Einstein - one would have to conclude that the process did not end up by producing creatures who were able to think, or at any rate, not always. What if, in reply, one were to be so vulgar as to offer a parody of Christian belief that was comparably low and uninstructed? It might read like this:

Christianity is a fighting religion. It thinks God made the world—that space and time, heat and cold, and all the colors and tastes, and all the animals and vegetables, are things that God ‘made up out of His head’ as a man makes up a story. But it also thinks that a great many things have gone wrong with the world that God made and that God insists, and insists very loudly, on putting them right again.

I would apologize for this pathetic caricature of faith-based life, if I had in fact written it. But it is Lewisʼ own best shot, and there is plenty more where that came from. He could knock out this stuff without even bothering to switch on what there was of his brain.

…Lewisʼ laughable and sinister book is a great joy and comfort to all those who have noticed the paper-thin morality and the correspondingly fanatical assertions of the religious. It should be a project of all skeptics and humanists and heretics to get it into the hands of as many readers as possible, most especially the young and impressionable. We, and not the “faithful” should be reprinting it and reaping the royalties.

[the above is all Hitchens, not me, speaking]

No comments:

Post a Comment