It was believed that people by the aid of the Devil could assume any shape they wished. Witches and wizards were changed into wolves, dogs, cats and serpents.

Within two years, between 1598 and 1600, in one district of France, the district of Jura, more than six hundred men and women were tried and convicted before one judge of having changed themselves into wolves, and all were put to death.

This is only one instance. There were thousands.

— Robert Ingersoll, “The Devil”

presbyter, noun.

- an elder in the early Christian Church.

- a minister or a lay elder in the Presbyterian Church.

- a minister or a priest in the Episcopal Church.

Source: “The Apocalypse of the Holy Mother”

Ante-Nicene Fathers; Volume 9; page 172

XIX

And she saw women hanging by their nails, and a flame of fire came out of their mouth and burned them: and all the beasts coming out of the fire gnawed them to pieces, and groaning they cried out: Have pity on us, have pity, for we are chastised worse than all those who are under chastisement. And seeing them the all holy one wept, and asked the commander-in-chief, Michael: What are these and what is their sin? And the commander-in-chief said: These are the wives of presbyters who did not honor the presbyters, but after the death of the presbyter took husbands, and for this cause they are thus chastised here.

So much for the Old and New Testaments saying a woman could marry again after her husband was deceased.

XX

And the all holy one saw after the same manner also a deaconess hanging from a crag and a beast with two heads devoured her breasts. (DO I SENSE AN UNSPOKEN LUST HERE?) And the all holy one asked: What is her sin? And the commander-in-chief said: She, all holy one, is an arch-deaconess who defiled her body in fornication, and for this cause she is thus chastised here.

XXI.

And she saw other women hanging over the fire, and all the beasts devoured them. And the all holy one asked the commander-in-chief: Who are these and what is their sin? And he said: These are they who did not do the will of God, lovers of money and those who took interest on accounts, and the immodest.

Itʼs a sin that “Men of God” should be able to call such filthy writings, “divinely inspired”.

Chelmsford Witches

Source: Encyclopedia of Witches and Witchcraft by Rosemary Ellen Guiley

Hanging of Three Chelmsford Witches

(English Pamphlet 1589)

Excerpt from www.thecryptmag.com

At Chelmsford, Essex in 1566, the first notable witch trial in England occurred. The charges against three defendants, Elizabeth Francis, Agnes Waterhouse and her daughter Joan were typical of most English trials as the highly imaginative stories of young children were accepted as evidence.

Agnes Waterhouse was hanged on July 29, 1566 (possibly the first woman hanged for witchcraft in England). Elizabeth Frances was imprisoned for a year, and then in 1579, she was charged with witchcraft again and hanged and Joan Waterhouse was found not guilty.

Another notable trial in Chelmsford occurred in 1589, which involved one man and nine women four were hanged and three were found not guilty.

Three of the witches were executed within two hours of sentencing: Joan Coney, Joan Upney and Joan Prentice.

A mass trial at Chelmsford took place in 1645, in which thirty-two women were accused and nineteen were hanged.

Devil Seducing Witch

Illustration for Ulrich Müller (Molotoris), Von den Unholden und Hexen

(Konstanz, 1489)

Source: “Demon Lovers” by Walter Stephens, The University of Chicago Press

Catholic Martyrdom - Heretics

Woodcut taken from “Salvation at Stake - Chapter: Catholic Martyrdom”

by Brad Gregory; Harvard University Press

“Thousands of men and women were executed for incompatible religious views in sixteenth-century Europe. The meaning and significance of those deaths are studied here comparatively for the first time, providing a compelling argument for the importance of martyrdom as both a window onto religious sensibilities and a crucial component in the formation of divergent Christian traditions and identities. Gregory explores Protestant, Catholic, and Anabaptist martyrs in a sustained fashion, addressing the similarities and differences in their self-understanding. He traces the processes and impact of their memorialization by co-believers, and he reconstructs the arguments of the ecclesiastical and civil authorities responsible for their deaths. In addition, he assesses the controversy over the meaning of executions for competing views of Christian truth, and the intractable dispute over the distinction between true and false martyrs. He employs a wide range of sources, including pamphlets, martyrologies, theological and devotional treatises, sermons, songs, woodcuts and engravings, correspondence, and legal records. Reconstructing religious motivation, conviction, and behavior in early modern Europe, Gregory shows us the shifting perspectives of authorities willing to kill, martyrs willing to die, martyrologists eager to memorialize, and controversialists keen to dispute.”

Urs Graf, Hermit and Devil (1512).

Pen and Ink Drawing.

Öffenliche Kunstsammlung Basel, .17.

Source: “Demon Lovers” by Walter Stephens, The University of Chicago Press

Hanging of Three Chelmsford Witches

(English Pamphlet 1589)

Source: Encyclopedia of Witches and Witchcraft

by Rosemary Ellen Guiley

Excerpt from www.controverscial.com

Matthew Hopkins and their familiars (Old Woodcut)

“The Witch-Finder General”

Written and compiled by George Knowles.

“Matthew Hopkins in perhaps the most notorious name in the history of English witchcraft, but more commonly he was known as “The Witch-Finder General”. Throughout his reign of terror 1644-1646, he was responsible for the condemnations and executions of some 230 alleged witches, more than all the other witch-hunters put together during the 160-year peak of the country's witchcraft hysteria.”

Hans Baldung Grien

“Naked Young Witch with Fiend in Shape of Dragon” (1515)

Source: “Demon Lovers” by Walter Stephens, The University of Chicago Press

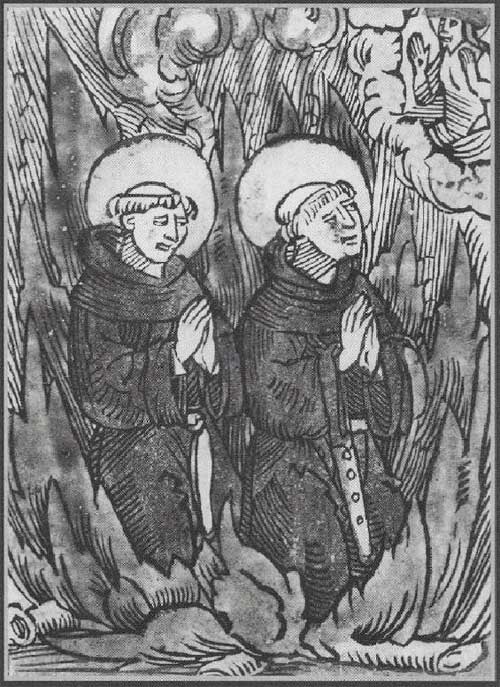

Christians being Burned Alive for Faith, by Christians

Woodcut taken from “Salvation at Stake” by Brad Gregory; Harvard University Press

“Thousands of men and women were executed for incompatible religious views in sixteenth-century Europe. The meaning and significance of those deaths are studied here comparatively for the first time, providing a compelling argument for the importance of martyrdom as both a window onto religious sensibilities and a crucial component in the formation of divergent Christian traditions and identities. Gregory explores Protestant, Catholic, and Anabaptist martyrs in a sustained fashion, addressing the similarities and differences in their self-understanding. He traces the processes and impact of their memorialization by co-believers, and he reconstructs the arguments of the ecclesiastical and civil authorities responsible for their deaths. In addition, he assesses the controversy over the meaning of executions for competing views of Christian truth, and the intractable dispute over the distinction between true and false martyrs. He employs a wide range of sources, including pamphlets, martyrologies, theological and devotional treatises, sermons, songs, woodcuts and engravings, correspondence, and legal records. Reconstructing religious motivation, conviction, and behavior in early modern Europe, Gregory shows us the shifting perspectives of authorities willing to kill, martyrs willing to die, martyrologists eager to memorialize, and controversialists keen to dispute.”

Martin Schongauer

"Temptation of Saint Anthony" (ca. 1470)

Source: “Demon Lovers” by Walter Stephens, The University of Chicago Press

Micheal Pacher, Saint Wolfgang and the Devil

From the Altarpiece of the Church Fathers (ca. 1475-79)

Source: “Demon Lovers” by Walter Stephens, The University of Chicago Press

Luca Signorelli, The Damned (ca.1503)

Orvieto Cathedral, Cappella Nuova (Cappella di San Brizio).

Source: “Demon Lovers” by Walter Stephens, The University of Chicago Press

“Werewolf”

Lucas Cranach Sr., Werewolf (ca 1510)

Source: “Demon Lovers” by Walter Stephens, The University of Chicago Press

The torture inflicted upon women accused of witchcraft was especially cruel.

Source: The Dark Side of Christian History, Helen Ellerbe

Hatred And Superstition Of Woman

“The process of formally persecuting witches followed the harshest inquisitional procedure. Once accused of witchcraft, it was virtually impossible to escape conviction. After cross-examination, the victim's body was examined for the witch's mark. The historian Walter Nigg described the process:”

…she was stripped naked and the executioner shaved off all her body hair in order to seek in the hidden places of the body the sign which the devil imprinted on his cohorts. Warts, freckles, and birthmarks were considered certain tokens of amorous relations with Satan.

Should a woman show no sign of a witch's mark, guilt could still be established by methods such as sticking needles in the accused's eyes. In such a case, guilt was confirmed if the inquisitor could find an insensitive spot during the process.

Confession was then extracted by the hideous methods of torture already developed during earlier phases of the Inquisition. “Loathe they are to confess without torture,” wrote King James I in his Daemonologie. A physician serving in witch prisons spoke of women driven half mad:

…by frequent torture…kept in prolonged squalor and darkness of their dungeons… and constantly dragged out to undergo autrocious torment until they would gladly exchange any moment this most bitter existence for death, are willing to confess whatever crimes are suggested to them rather than to be thrust back into their hideous dungeon amid ever recurring torture.

Unless the witch died during torture, she was taken to the stake. Since many of the burnings took place in public squares, inquisitors prevented the victims from talking to the crowds by using wooden gags or cutting their tongues out. Unlike the heretic or a Jew who would usually be burnt alive only after they had relapsed into their heresy or Judaism, a witch would be burnt upon the first conviction.

Sexual mutilation of accused witches was not uncommon. With the orthodox understanding that divinity had little or nothing to do with the physical world, sexual desire was perceived to be ungodly. When the men persecuting the accused witches found themselves sexually aroused, they assumed that such desires emanated, not from themselves, but from the woman. They attacked breasts and genitals with pincers, pliers and red-hot irons. Some rules condoned sexual abuse by allowing men deemed “zealous Catholics” to visit female prisoners in solitary confinement while never allowing female visitors. The people of Toulouse were so convinced that the inquisitor Foulques de Saint-George arraigned women for no other reason than to sexually abuse them that they took the dangerous and unusual step of gathering evidence against him.

Source: The Dark Side of Christian History, Helen Ellerbe, pg. 123, 124

Old and poor women were most often the first accused of witchcraft.

Source: The Dark Side of Christian History, Helen Ellerbe

“The most common victims of witchcraft accusations were those women who resembled the image of the Crone. As the embodiment of mature feminine power, the old wise woman threatens a structure which acknowledges only force and domination as avenues of power. The Church never tolerated the image of the Crone, even in the first centuries when it assimilated the prevalent images of maiden and mother in the figure of Mary. Although any woman who attracted attention was likely to be suspected of witchcraft, either on account of her beauty or because of a noticeable oddness or deformity, the most common victim was the old woman. Poor, older women tended to be the first accused even where witch hunts were driven by inquisitional procedure that profited by targeting wealthier individuals.

Old, wise healing women were particular targets for witch-hunters. “At this day,” wrote Reginald Scot in 1584, “it is indifferent to say in the English tongue, ‘she is a witch’ or ‘she is a wise woman’.” Common people of pre-reformational Europe relied upon wise women and men for the treatment of illness rather than upon churchmen, monks or physicians. Robert Burton wrote in 1621:

“Sorcerers are too common; cunning men, wizards and white witches, as they call them, in every village, which, if they be sought unto, will help almost all infirmities of body and mind.”

“By combining their knowledge of medicinal herbs with an entreaty for divine assistance, these healers provided both more affordable and most often more effective medicine than was available elsewhere. Churchmen of the Reformation objected to the magical nature of this sort of healing, to the preference people had for it over the healing that the Church or Church-lisenced physicians offered, and to the power it gave women.

“Witch Giving Ritual Kiss to Devil”

From Francesco Maria Guazzo, Compendium maleficarum 2d ed.

(Milan, 1626)

Source: “Demon Lovers” by Walter Stephens, The University of Chicago Press

Urs Graf, Four Witches and Cat (1514)

Chapter 10, Part II

“Witches Who Steal Penises” in “Demon Lovers”

Source: “Demon Lovers” by Walter Stephens, The University of Chicago Press

No comments:

Post a Comment