Hypatia (370?-415 A.D.), Greek philosopher, born in Alexandria, daughter of the mathematician Theon (q.v.). She assisted her father in his writings, and succeeded him as lecturer on mathematics and Greek philosophy. Her intellectual gifts and her beauty attracted students from foreign countries; and her judgment was so respected that the city magistrates of Alexandria consulted her on important cases. In about 400 A.D. she was the undisputed leader of the Neoplatonic school of philosophy at Alexandria (see Neoplatonism). She was the author of commentaries on ancient astronomical and mathematical works. Because of her association with Orestes, the pagan prefect of Alexandria who opposed the persecution of the Jews and other non-Christians initiated by Bishop Cyril (see Cyril, Saint), Hypatia was murdered by a mob of Christians and her body was burned. She is the heroine of the historical romance Hypatia (1853) by the English novelist Charles Kingsley.

Source:Funk and Wagnalls Encyclopedia 1950 and 1951

III.-The Policy Of Succeeding Emperors Toward Heathenism.

The discretion of the emperor who followed Julian saved Christian rule, for the time being, from an unfavorable contrast with heathen rule, as respects tolerance.

Jovian earned the hearty encomiums of representative heathens, such as Themistius, by granting full liberty for the exercise of their religion, those obnoxious rites alone excepted for which no one expected a governmental sanction. Valentinian, Emperor of the West from 364 to 375, adhered in general to the same principles; a superstitious zeal in prosecuting those suspected of practicing magic being his most serious exhibition of intolerance. Valens (364-378), Emperor of the East, by the grace of his brother Valentinian, acknowledged the same laws in relation to heathenism, and sanctioned a similar severity against all supposed to be guilty of magic and divination. The reputation for intolerance attached to Valens is due rather to the rigor with which, as an Arian, he treated the orthodox party, than to any violent attack upon heathenism, It was during the joint reign of these emperors that the word paganism was first employed officially as a designation of a religion. l

1 codex Theodus., Lib XVI., Tit. ii. 18.

Gratian, who followed Valentinian in the rule of the West, while he issued no sweeping prohibition against the practice of heathenism, dealt it a destructive blow by ordering that the revenues of the temples, and the public support which had been given to priests and vestals, should be withdrawn, He also commanded the statue and altar of Victory to be removed from the Senate. A strong effort was made by heathen partisans to have these measures repealed; but the diligence and energy of Ambrose, who was highly influential both with Gratian and his successor, Valentinian II., defeated the attempt.

In 379 Theodosius came to the throne of the East, and in 394 his success in overthrowing the usurper Eugenius gave him also the rule over the West. Reversing the policy of Valens in relation to the doctrinal controversies of the age, he assisted the orthodox party to a final victory. As regards heathenism, his decrees and his practice indicated for a considerable time a wavering between toleration and proscription; but in 891 he entered decidedly upon a policy of total repression, that is, of heathen rites. The mere belief, or even its advocacy, he did not think of touching, and numbered professed heathen among his friends and officers. By a law of 392, the offering of idolatrous sacrifices was declared a crimen majestatis, and as such might be capitally punished. This penalty, however, had its place in the statute-book, rather than in actual execution. “The ready obedience of the pagans,” says Gibbon, “protected them from the pains and the penalties of the Theodosian code.” l

1 Chap xxviii

But if their persons were spared, their temples in many instances were not. No general edict was issued by Theodosius for their destruction; but the passions of the populace, and the fanatical zeal of the monks, urged on, in various districts, the work of spoliation and ruin. In some cases retaliation was provoked from the heathen. We read of Christian churches being burned in Palestine and Phoenicia. In Alexandria the heathen requited what they deemed an insult to their faith (namely, an ostentatious parading of the indecent symbols found in a temple which had been devoted to the worship of Bacchus) with violence and bloodshed; and, indeed, they so far committed themselves by their sedition, that they finally counted it good fortune that they were allowed to escape with their lives, though obliged to witness the destruction of the magnificent temple of Serapis, as well as of less noted edifices.

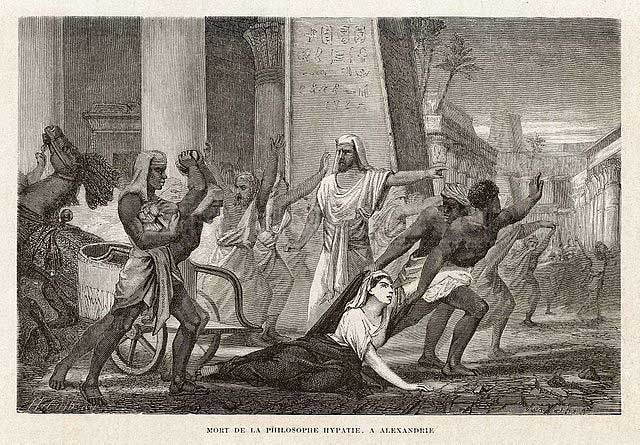

A similar course, attended with similar incidents, was pursued by the sons of Theodosius, Arcadius, and Honorius, and by their immediate successors. The episode most disgraceful to the Christian side was the murder at Alexandria, in 415, of the beautiful and talented female philosopher Hypatia. It is to be observed, however, that, while professed Christians were the agents in this brutal and unchristian deed, it was not altogether in the name of religion that it was accomplished. Political motives were prominent. The deed, moreover, was that of a mob, -a mob drawn from a populace noted for its turbulence and ferocity. “The Alexandrians,” says Socrates, who was in middle life at the time of the tragedy, “are more delighted with tumult than any other people; and if they can find a pretext they will break forth into most intolerable excesses.” The same historian speaks in the highest terms of the character and ability of Hypatia, representing her as gaining universal admiration by her dignified modesty of deportment, as drawing students from a great distance to hear her exposition of the Neo-Platonic philosophy, and as surpassing all the philosophers of her time through her attainments in literature and science, “Yet even she fell a victim,” he continues, “to the political jealousy which at that time prevailed. For as she had frequent interviews with Orestes [the prefect], it was calumniously reported among the Christian populace that it was by her influence he was prevented from being reconciled to Cyril. Some of them, therefore, whose ringleader was a reader named Peter, hurried sway by fierce and bigoted zeal, entered into a conspiracy against her; and observing her as she returned home in her carriage, they dragged her from it, and carried her to a church called Caesareum, where they completely stripped her, and murdered her with shells. After tearing her body in pieces, they took her mangled limbs to a place called Cinaron, and there burned them. An act so inhuman could not fail to bring the greatest opprobrium, not only upon Cyril, but also upon the whole Alexandrian Church.” The judgment which the Christian historian passes upon the deed, it may fairly be presumed, was the judgment of intelligent and sober-minded Christians the Empire over.

As heathenism had very little to contend for, it gradually succumbed. Only a remnant of it was left in the East by the time of Justinian (527-565), and to this the despotic emperor endeavored to give a finishing blow. Heathen worship was declared by him a capital offence, and its last source of intellectual prestige was quenched by the abolition of the philosophical school of Athens. In the West, the incursions of the barbarians left little chance for the exercise of any central and decisive authority on the subject. But as the Barbarians themselves had no favor for the old classic heathenism, it found no refuge, save in the hearts of occasional devotees in the cities, and in the rites which might safely be practiced in the unfrequented districts.

History of the Christian Church; Vol. 1 “The Early Church” pages 362-366

By Henry C. Sheldon, New York, 1895

A speech given before the Independent Religious Society at the Majestic Theater in Chicago

The Martyrdom of Hypatia (or The Death of the Classical World)

by Mangasar Magurditch Mangasarian

Mangasar Mugurditch Mangasarian 1859-1943,

Mangasarianʼs lectures Chicago : s.n., 1912-1919 (v. ; 22 cm)

Series: Rationalist (Independent Religious Society of Chicago), v. 1-4

Mangasar Mugurditch Mangasarian 1859-1943,

“The martyrdom of Hypatia, or, The death of the classical world.”,

The Rationalist, May 1915

Our subject this morning takes us to the city of Alexandria, one of the greatest intellectual centers in the days when Athens and Rome still ruled the world. The capital of Egypt received its name from the man who conceived and executed its design — Alexander the Great. Under the Ptolemies, a line of Greek kings, Alexandria soon sprang into eminence, and, accumulating culture and wealth, became the most powerful metropolis of the Orient. Serving as the port of Europe, it attracted the lucrative trade of India and Arabia. Its markets were enriched with the gorgeous silks and fabrics from the bazaars of the Orient. Wealth brought leisure, and it, in turn, the arts. It became, in time, the home of a wonderful library and schools of philosophy, representing all the phases and the most delicate shades of thought. At one time it was the general belief that the mantle of Athens had fallen upon the shoulders of Alexandria.

But there was a stubborn and superstitious Oriental constituency in the city which would not blend with the foreign element — namely, the Greeks and the Romans. This antagonism between the Egyptian born and the children of Hellas and Rome, who were Alexandrians only by adoption, was frequently the occasion of street riots, feuds, massacres, and civil wars.

In or about the year 400 A.D., Alexandria, which is today a third-rate Mohammedan town, enjoyed a population of 600,000 inhabitants. The city proper comprehended a circumference of fifteen miles. It enjoyed the distinction of being quite free from the curse of poverty. No beggars could be seen loitering in its streets. No one was idle, and work brought good wages. Such was the demand for labor that even the lame and the blind found suitable occupation. The Alexandrians understood the manufacture of papyrus, a kind of vegetable paper used extensively by the authors, and they knew how to blow glass and weave linen.

After its magnificent library, whose shelves supported a freight more precious than beaten gold, perhaps the most stupendous edifice in the town was the temple of Serapis. It is said that the builders of the famous temple of Eddessa boasted that they had succeeded in creating something which future generations would compare with the temple of Serapis in Alexandria. This ought to suggest an idea of the vastness and beauty of the Alexandrian Serapis, and the high esteem in which it was held. Historians and connoisseurs claim it was one of the grandest monuments of Pagan civilization, second only to the temple of Jupiter in Rome, and the inimitable Parthenon in Athens, which latter is certainly the best gem earth ever wore upon her zone.

The Serapis temple was built upon an artificial hill, the ascent to which was by a hundred steps. It was not one building, but a vast body of buildings, all grouped about a central one of vaster dimensions, rising on pillars of huge magnitude and graceful proportions. Some critics have advanced the idea that the builders of this masterpiece intended to make it a composite structure, combining the diverse elements of Egyptian and Greek art into a harmonious whole. The Serapion was regarded by the ancients as marking the reconciliation between the architects of the pyramids and the creators of the Athenian Acropolis. It represented to their minds the blending of the massive in Egyptian art with the grace and the loveliness of the Hellenic.

But the greatest attraction of this temple was the god Serapis himself, within the vaulted building. It is difficult for us to form an idea of his enormous proportions. He filled the house with his presence. He stretched his arms and took hold of the two walls, the one on his right and the other on his left. The artist had conceived, also, the idea of making the body of the god as all-embracing as his arms. He fused together all the then known metals — gold, silver, copper, iron, tin, lead — to create a substance fit to represent a god. He inlaid this multifarious composition with the rarest gems — the most costly stones which the markets of the world offered. He polished them all until the colossal statue shone like a huge sapphire. Its exquisite tints and shades are said to have provoked the jealousy of the azure skies. For a crown, the god wore on his head a bushel, symbol of plentiful harvests. At his side, in silence, stood a three-headed animal with the forepart of a lion, a wolf, and a dog. The lion was meant to represent the present; the rapacious wolf symbolized the past — the devoured past; while the dog, the faithful, friendly animal, stood for the future. Wound around the body of the god was a mammoth serpent, which, after its many turns and twists, returned to rest his head on the hand of the god. The sinuous serpent was meant to personate Time, whose mysterious birthplace, or birthday, has yet to be discovered.

Serapis, whose statue adorned the temple, was once the most popular god in the Orient. He was believed to be the source of the Nile, whose breasts he swelled until they poured their wealth upon the surrounding soil. As long as his eye remained open, the sun would shine, and the land would produce, and women would give birth. But if he should close his eye, life would became as a sere and sapless leaf. But Serapis was a stranger in Egypt. He was not an African by birth, but was imported from Sinope, on the Euxine. When he first made his appearance in the land of the Nile, the people — the Alexandrians, especially — rose up en masse and protested vehemently against the introduction of a foreign deity. Did they not have Osiris, the great god of their ancestors, and Isis, his consort — the divine woman with her infant, Horus, sitting upon her knees? Why, then should a strange god be admitted to the throne or to the bed of Osiris and Isis? Did they not have their holy trinity, Osiris, Isis, and Horus — father, mother, and child — the best trinity ever conceived? But Ptolemy was king, and his will prevailed. He told them that Osiris had, in a dream, commanded him to accept Serapis as a new and well-beloved god, and he did not wish to do anything contrary to his dream.

In all this do we not see a similarity to the story about Jesus, and how his friends compelled solitary Jehovah to accept him as his son, and share with him the honors of divinity? We know how the people objected at first to Jesus, precisely as the Alexandrians did to Serapis, and how, finally, through dreams and miracles, Jesus, the new God, grew to be even more popular than the old one.

When Christianity gained the upper hand in Alexandria, it set its mind from the start upon destroying two of the principal monuments of its powerful rival, Paganism — the library and the temple of Serapis. Let me at this juncture remind you that Alexandria, at a very early period, became one of the foremost strongholds of the Christian religion. Of the five capitols of the new faith — Jerusalem, Constantinople, Carthage, Alexandria, Rome — Alexandria at one time led Constantinople, and was not second even to Rome. What was said about Christianity being essentially an Asiatic philosophy is confirmed, it seems to me, by this additional fact; that out of five of its greatest centers four were in the Orient. It felt more at home in Asia and Africa than in Europe. A still stronger confirmation of the affinity between Asia and Christianity is the fact that as soon as the Roman Empire became Christian it shifted its capital from Europe to Asia, from Rome to Constantinople. The first Christian emperor, Constantine, impelled, as it were, by the logic of his new religion, left Rome to take up his residence on the Bosphorus, which washed the shores of the continent that had cradled Christianity. For a ruler who coveted absolute power, who feared democracy, who hated liberty and who preferred stagnation of thought to the movement of ideas, who desired slaves for subjects, Asia was the more suitable place. Without wishing to offend anyone, I must say that Christianity was more Asiatic than Paganism, and the Orient was better fitted to be the home of political and religious absolutism than the occident. Christianity, as the religion of meekness and obedience, had irresistible attractions for Constantine. He not only embraced it, but he went to dwell as close to where its cradle had swung as he could.

It is not the fault of Christianity that the Asiatic is servile, but the fault of the Asiatic that Christianity is so supple and submissive. It is not so much religion that makes the character of a people, as it is the people who determine the character of their religion. Religion is only the resume of the national ideas, thoughts, and character. Religion is nothing but an expression. It is not, for instance, the word or the language which creates the idea, but the idea which provokes the word into existence. In the same way religion is only the expression of a peopleʼs mentality. And yet a manʼs religion or philosophy, while it is but the product of his own mind, exerts a reflex influence upon his character. The child influences the parent, of whom it is the offspring; language affects thought, of which, originally, it was but the tool. So it is with religion. The Christian religion, as soon as it got into power, turned the world about. It struck at the Roman Empire, and grabbing everything it could lay its hands on — the scepter, the sword, the imperial diadem, the throne — it walked away with them to Asia. We could never ask for a more eloquent defense of the position that Christianity is Asiatic than is found in this historic transfer of the seat of power from Europe to Asia, from Rome to Constantinople.

Now, naturally enough, a religion which combats the culture and traditions of European life in Europe, will not tolerate them in Asia. Do we understand this point? If it seeks to down European thought in Europe, how much more will it seek to expel it from Asia? If it persecutes Socrates, Plato, Cicero, and Seneca in Europe, it cannot, of course, tolerate them in Asia. Christianity tried to destroy all the monuments of Paganism in Rome, in free and proud Rome; could it, then, leave them standing in Alexandria, in Constantinople, or in Antioch? On the contrary, in Asia, which is her proper home, the seat of her power, and with the Emperor transferred to Constantinople, Christianity became more aggressive against Paganism and civilization than even in Europe. Religion, like everything else, is consistent as long as it is young and virile, and Christianity in the early centuries was both young and virile, and therefore logical. Changing slightly the great words of Shakespeare, we might say:

There is a logic which shapes our ends

Rough hew them as we may.

We wonder sometimes that a Japanese gentleman or an Arab, or a Siamese, who has never mingled with Europeans or Americans, should think as we do, or exhibit the polite manners of occidental races. There are those who refuse to believe that a Pagan, living three thousand years ago, could possess the very virtues which we prize today. The sectarian who believes that only people of the size and caliber of his creed can be good, is at a loss to explain the universality of culture and virtue. This is explained by his inability to perceive that there is a logic in the development of the human being which brings about the same results the world over — before Christ, and after. Let us appreciate this truth. How can a Moslem or a Jew or a Pagan be as good as a Christian? By a law of nature and evolution the ripened human fruit is the same the world over. If only Mohammedanism or Christianity or Judaism possessed the power to make men good, then there would be no morality outside these religions. But history contradicts so sweeping a conclusion. There is a logic, we repeat, in the culture of the mind which makes a Trajan, who was a Pagan, as sweet and sane as a Washington, who was born in a Christian era, or the Chinese Confucius, as noble and independent as the French Voltaire. I say there is a universality in the evolution of man, before which all sectarian pretenses and conceits are like chaff for the wind to sport with. And we cannot be really large-minded, nor can we read history and philosophy aright, until we appreciate the power of the logic which shapes our ends “rough hew them as we may.”

The transference of the capital of the world and the seat of authority from Europe to Asia was not an accident. It was a logical step. Christianity, to be consistent, had to break up housekeeping in Europe and move its menage from Rome to Constantinople. She was homesick for the climate, the atmosphere, the peoples, the traditions, the spirit, the institutions — the milieu in which she was born. Unable to assimilate western ideas, she pined for Asia. By the same logic, she wished to wipe out in Asia every trace of European thought and culture. When, therefore, we read of the destruction of Pagan schools, libraries, and monuments, let us not look upon such acts as accidents in the history of Christianity, but as the logical unfolding of its genius. Why, you may ask, does it no longer pursue the policy of extermination? For the best of reasons; it is no longer virile enough to be logical. It has stumbled into the ways of inconsistency by reason of old age. Fifteen hundred years ago, in Alexandria, when our religion was both young and lusty, it attempted to, and succeeded in, destroying everything that reminded the world of the glory and liberty of ancient Rome and Greece.

Theodosius was at the time, of which we will now speak, the Christian ruler of the Empire. In reply to a request by the Archbishop of Alexandria, he sent a sentence of destruction against the ancient religion of Egypt. Both the Pagans and the Christians had assembled in the public square to hear the reading of the Emperorʼs letter, and when the Christians learned that they may destroy the gods of the Pagans, a wild shout of joy rent the air. The disappointed Pagans, on the other hand, realizing the danger of their position, silently slipped into their homes through dark alleys and hidden passage-ways. Yet they did not stand aside and see the temples of their gods razed to the ground without first offering a desperate resistance. Under the leadership of a zealot, Olympus, the Pagans fell upon the Christians, maddened with the cry in their ears of their leader, “Let us die with our gods!” Then came the turn of the Christians. Theophilius, the Archbishop of Alexandria, with a cross in his hand, and followed by his monks, marched upon the temple of Serapis, and proceeded to pull its pillars down. When they came to strike at the colossal statue of the god, for centuries worshiped as a deity, even the Christians turned pale with superstitious awe, and held their breath. A soldier armed with a heavy axe, was hesitating to strike the first blow. Will the god tolerate the insult? Will he not crash the roof upon the heads of the sacrilegious vandals? But the soldier struck the thundering blow right in the cheeks of Serapis, who offered no remonstrance whatever. The sun shone as usual, and the laws of nature maintained their even pace. Encouraged by this indifference of the god to defend himself, the Christian rabble rushed upon the statue, and pulling Serapis off his seat, dragged him in pieces through the streets of Alexandria that the Pagans might behold the disgrace into which their great god had fallen. Thousands of Pagans, seeing how helpless their gods were to avenge this insult, deserted Paganism and joined the Christians. As soon as the ground of the temple was sufficiently cleared, a church was erected on the ancient site. The Alexandrian library was the next point of attack. Its shelves were soon cleared, and you and I, and twenty centuries, were most lamentably deprived of the intellectual treasures which our Greek and Roman forefathers had bequeathed unto us.

When the archbishop under whose influence the monuments and libraries of Pagan civilization were pillaged and pulled down died, he was succeeded by his nephew, St. Cyril, who was even more Asiatic in his sympathies and more hostile to European thought than his uncle, Theophilius. The new archbishop directed his efforts against the living monuments of Paganism — the scholars, the poets, the philosophers — the men and women who still cherished a passionate regard for the culture and civilization of the Pagan world. The most illustrious representative of Greco-Roman culture in Alexandria about this time was Hypatia, the gifted daughter of Theon, a mathematician and a philosopher of considerable renown. It is said that Theon would have come down to us as a great man had not his daughterʼs fame eclipsed his.

Hypatia was a remarkably gifted woman. Her example demonstrates how all difficulties yield to a strong will. Being a girl, and excluded by the conventions of the time from intellectual pursuits, she could have given many reasons why she should leave philosophy to stronger and freer minds. But she had an all-compelling passion for the life of the mind, which overcame every obstacle that interfered with her purpose. The example of a young woman conquering tremendous difficulties, and becoming the undisputed queen of an intellectual empire, ought to be a great inspiration to us faint hearts. She won the prize which was denied her sex, and became “the glory of her age and the wonder of ours.”

To pursue her studies, she persuaded her father to send her to Athens, where her earnest work, her devotion to philosophy, the readiness with which she sacrificed all her other interests to the cultivation of her mind, earned for herself the laurel wreath which the university of Athens conferred only upon the foremost of its pupils. Hypatia wore this wreath whenever she appeared in public, as her best ornament. Upon her return to Alexandria, she was elected president of the Academy, which at this period was the rendezvous of the leading minds of the East and West. In fact, it was in this academy that the effort of the advanced thinkers to bring about a pacification between the culture of Europe and that of Asia originated. They wished to make Alexandria, situated midway between the occident and the orient, the point of confluence of the two streams of civilization. They wished to celebrate the marriage of the East as bride to the West as bridegroom. It was their plan to make Alexandria a sort of intellectual distillery, refining and fusing the two civilizations into one. But this amalgamation — this assimilation — Christianity, alas, helped to prevent by bringing into still bolder relief the Asiatic habits of mind, and by refusing to concede an inch to the larger spirit of the West. Christianity is responsible for the miscarriage which has ever since left Asia a widow, or, to change the simile, a withered branch upon the tree of civilization. Christianity broke the link which scholarship and humanity were trying to forge between Europe and Asia. The world has never since been one as it came near being under the Roman Empire.

Cyril, the Archbishop of Alexandria, persuaded himself that Hypatiaʼs good name and talents were giving the cause of Paganism a dangerous prestige, and thereby preventing the progress of the new faith. Hypatia was indeed a great power in Alexandria. She was the most popular personage in the city. When she appeared in her chariot on the streets people threw flowers at her, applauded her gifts, and cried, “Long live the daughter of Theon.” Poets called her the “Virgin of Heaven,” “the spotless star,” “of highest speech the flower.” Judging by the chronicles of the times, it appears that her beauty, which would have made even a Cleopatra jealous, was as great as her modesty, and both were matched by her eloquence, and all three surpassed by her learning.

Her beauty did astonish the survey of eyes,

Her words all ears took captive.

Her renown as a lecturer on philosophy brought students from Rome and Athens, and all the great cities of the empire, to Alexandria. It was one of the great events of each day to flock to the hall in the academy where Hypatia explained Plato and Aristotle. Cyril, the Asiatic archbishop, passing frequently the house of Hypatia, and seeing the long train of horses, litters, and chariots which had brought a host of admirers to the female philosopherʼs shrine, conceived a terrible hatred for this Pagan girl. He did not relish her popularity. Her learning was rubbish to him. Her charms, temptations for the ruin of man. He hated her because she, a frail woman, dared to be free and to think for herself. He argued in his mind that she was competing with Christianity, taking away from Christ the homage which belonged to him. With Hypatia out of the way the people would turn to God, and give him the love and honor which they were wasting upon her. She was robbing God of his rights, and she must fall; for He is a jealous God. Such was the reasoning of Cyril, whom the Church has canonized.

Moreover, Orestes, the Prefect of Alexandria, respected Hypatia, and was a constant attendant at her lectures. Cyril believed that she influenced the Prefect and tainted him with her Paganism. With Hypatia crushed, Orestes would be more responsive to Christian influences. Ah, it is a cruel story which I am about to unfold. Generally speaking, if a man is jealous and small, no religion can make him sweet; and if he is generous and pure-minded, no superstition can altogether poison the springs of his love. Religion is strong, but nature is stronger. Unfortunately Cyril was a barbarian, and the doctrines of his religion only sharpened his claws and whipped his passion into a rage.

If we were living in those days we would have witnessed at the close of each day, when both sea and sky blush with the departing kiss of the sun, Hypatia mounting her chariot to ride to the academy, where she is announced to speak on some philosophical subject. She is followed by many enthusiastic and devoted admirers impatient to catch her eye. She is nodding to her friends on her right and on her left. She, who refused lovers that she may love philosophy, is not insensible to the appreciation of her pupils. Approaching the academy, she dismounts, ascends the white marble steps and enters by the door, on either side of which sit two silent sphinxes. As we follow her into the hall, we see that it is lighted by numerous swinging lamps filled with perfumed oil; the rotunda of the ceiling has been embellished by a Greek artist, with figures of Jupiter and his divine companions, who appear to be rapt in the words which fall from his lips. The walls have been decorated by Egyptian artists, with pictures of the sacred animals, the crocodile, the cat, the cow, and the dog; and with sacred vegetables, the onion, the lotus, and the laurel. Besides these there is a scene on the walls representing the marriage of Osiris and Isis. On an elevated platform is a divan in purple velvet, and upon a little table is placed the silver statue of Minerva, goddess of wisdom and patron of Hypatia. Behind the table sits the philosophic young woman dressed in a robe of white, fastened about her throat and waist by a band of pearls, and carrying upon her brow the laurel crown which Athens had decreed to her. A musical murmur sweeps over the audience as she rises to her feet. But in a moment all is silent again save the throbbing and trembling of Hypatiaʼs silvery voice. She speaks in Greek, the language of thought and beauty, of the ancient world. Alas! this is her last appearance at the academy. Tomorrow that hall will be a tomb. Tomorrow Minerva will be childless. When Hypatiaʼs listeners bade her farewell on that evening they did not know that within a few hours they would all become orphans.

The next morning, when Hypatia appeared in her chariot in front of her residence, suddenly five hundred men, all dressed in black and cowled, five hundred half-starved monks from the sands of the Egyptian desert — five hundred monks, soldiers of the cross — like a black hurricane, swooped down the street, boarded her chariot, and, pulling her off her seat, dragged her by the hair of her head into a — how shall I say the word? — into a church! Some historians intimate that the monks asked her to kiss the cross, to become a Christian and join the nunnery, if she wished her life spared. At any rate, these monks, under the leadership of St. Cyrilʼs right-hand man, Peter the Reader, shamefully stripped her naked, and there, close to the alter and the cross, scraped her quivering flesh from her bones with oyster shells. The marble floor of the church was sprinkled with her warm blood. The alter, the cross, too, were bespattered, owing to the violence with which her limbs were torn, while the hands of the monks presented a sight too revolting to describe. The mutilated body, upon which the murderers feasted their fanatic hate, was then flung into the flames.

Oh! is there a blacker deed in human annals? When has another man or woman been so inhumanly murdered? Has politics, has commerce, has cannibalism even committed a more cruel crime? The cannibal pleads hunger to cover his cruelty — what excuse had Hypatiaʼs murderers? Even Joan of Arc was more fortunate in her death than this daughter of Paganism! Beautiful woman! murdered by men who were not worthy to touch the hem of thy garment! And to think that this happened in a church — a Christian church!

I have seen the frost bite the flower; I have watched the spider trap the fly; I have seen the serpent spring upon the bird! And yet I love nature! But I will never enter a church nor profess a religion which can commit such a deed against so lovable a woman. No, not even if I were offered as a bribe eternal life! If, O priests and preachers! instead of one hell, there were a thousand, and each hell more infernal than your creeds describe, yet I would sooner they would all swallow me up, and feast their insatiable lust upon my poor bones for ever and ever, than lend countenance or support to an institution upon which history has fastened the indelible stigma of Hypatiaʼs murder!

I wish I could live a thousand years to admire the noble spirit and delight in the courage and beauty of this brave martyr of Philosophy, Hypatia! O that my voice were strong enough to reach the ends of the world! I would then summon all independent minds to join with me in a hymn of praise to that incomparable woman, who has joined the choir invisible and Whose music is the gladness of the world.

Honor and love to beautiful Hypatia! Pity to the monks who killed her! A delicious feeling of satisfaction, like a warm sunshine on a wintry day, spreads over me as I contemplate the privilege I am enjoying of vindicating her memory against her assassins. Fortune has smiled upon me in selecting me as one of her defenders. I congratulate myself on having both the heart and the head to weep over her sad fate. And I tremble and shrink, as from a paralyzing nightmare, when I think that, under different circumstances, I might still have a minister of the Church whose hands are, after fifteen hundred years, still unwashed of her innocent blood. The thought overpowers me; I labor for breath. But I am free. O joy, O rapture! I am free to speak the truth about Hypatia. Let the clergy praise Peter and Paul, St. Cyril and St. Theophilius. I give my heart to thee, thou glorious victim of superstition!

If we, of this present generation, are responsible for Adamʼs sin, and deserve the penalties of his disobedience, as the clergy say we do, then the Church of today is responsible for Hypatiaʼs fate. How will they take this practical application of their own dogma? It will not do for them to say: “We wash our hands clean of St. Cyrilʼs sin”; for if Adam can, by his remote act, expose us all to damnation, so shall Bishop Cyrilʼs dark deed cleave for ever unto the religion which his followers profess. Yet, let the Church people apologize, and we shall forgive them; but no apology short of discarding this Asiatic slave-creed, which in the Old Testament stoned the free thinker to death, and in the New pronounces him a “heathen and a publican,” will satisfy the ends of justice.

I have intimated, by the wording of my subject, that it was a classic world which was murdered in the person of one of its last and noblest representatives, Hypatia. Hypatia embodied in her life and teaching, the proud spirit, the beauty, the culture, and the sanity of Greece. With her, fell Greece; fell the intellectual world from her eminence.

Then followed the nearly ten centuries of Egyptian darkness, which settling over Europe, paralyzed all initiative. During the thousand years in which the spirit of St. Cyril and his Church managed, with undisputed sway, the affairs of religion and the State, night folded to its sterile bosom our orphaned humanity, and the chains of slavery were upon every mind. A cloud of dust rising heaven-high choked the flow and dried up the fountains which had, in the days of Pericles and Antoninus, poured forth a world of living waters. The barren and lumbering theology of the Church crowded out the Muses from their earthly walks, and the world became a prison after having been the home of man. One by one the great lights went out; Athens was no more, Rome was dead. The bloom had vanished from the face of the earth, and in its place there fell upon it the awful shadow of a future hell.

Symonds, in his “The Greek Poets,” says that while Cyrilʼs mobs were dismembering Hypatia, the Greek authors went on creating, “Musaeus sang the lamentable death of Leander, and Nonnus was perfecting a new and more polished form of the hexameter.” These authors, ignorant that the Asiatic superstition had destroyed their world, or that they had themselves been stabbed to death — like one who has been shot, but whose wound is still warm, and who does not know that he has but a few more breaths to draw — kept on singing their song. But their song was, indeed, the “very swanʼs notes” of the classical world. “With the story of Hero and Leander, that immortal love poem, the Muse,” says the same author, “took her final farewell of her beloved Hellas.”

After a thousand years of night, when the world awoke from her sleep, the first song it sang was the last long of the dying Pagan world. This is wonderfully strange. In the year 1493, when the Renaissance ushered in a new era, the first book brought out in Europe was the last book written in Alexandria by a Pagan. It was the poem of Hero and Leander. The new world resumed the golden thread where the old world had lost it. The severed streams of thought and beauty met again into one current, and began to sing and shine as it rushed forth once more, as in the days of old. A Greek poem was the last product of the Pagan world; the same Greek poem was the first product of the new and renascent world.

Between the dying and reviving Pagan world was the Christian Church — that is to say, ten dark centuries.

If Greece and Rome made art, poetry, philosophy, sculpture, the drama, oratory, beauty, (and) liberty classical, (then) Christianity the Syrian, Asiatic cult made for nearly fifteen hundred years persecution, religious wars, massacres, theological feuds and bloodshed, heresy huntings and heretic burnings, prisons, dungeons, anathemas, curses, opposition to science, hatred of liberty, spiritual bondage, the life without love or laughter, a classic!

But the dawn is in the sky, and it is daybreak everywhere!

We are reasonably confident that never again will this religion, born and bred in Asia, command sufficient influence over the minds of modern men to burn or murder the intellectual aristocrats, the daily beauty of whose lives makes the ugliness of superstition so very noticeable. What a difference there would have been in our attitude toward the Christian Church, if, instead of fearing the thinker and the inquirer, and persecuting him with a hatred too awful to contemplate, it had opened both its arms to welcome him with affection and gratitude! But the “divine” is always jealous of the human. Hypatia eclipsed the glory of God. She was murdered because only “the poor in spirit” — the intellectual babes, are the elect of Heaven.

It is good news, however, that while the Church may still exclude the mental giants from the world to come, it can no longer exclude them from the world that now is!

“All formal dogmatic religions are fallacious and must never be accepted by self-respecting persons as final. Reserve your right to think, for even to think wrongly is better than not to think at all. To teach superstitions as truth is a most terrible thing.”

- Theon to Hypatia of Alexandria

Murder of Hypatia and the burning of the Great Library at Alexandria

Mathematicians: Hypatia of Alexandria

The persecution and murder of Hypatia was a transformative event. After Hypatia, the stature of women, which had been enhanced via involvement in Pagan systems of worship, was significantly diminished. In the end:“They dragged her along till they brought her to the great church, named Caesarion. Now this was in the days of the fast. And they tore off her clothing and dragged her through the streets of the city till she died. And they carried her to a place named Cinaron, and they burned her body with fire…”

No comments:

Post a Comment